When juror Hazel Thornton was chosen for the 1993 Menendez brothers trial, she had no idea she would be thrust into one of the most high-profile cases.

What she had once thought was an open-and-shut case turned into a grueling courtroom saga marked by emotional clashes and complex family dynamics.

“I had heard a rumor on the morning of the first day that it was Menendez, but I hadn’t been called to a panel yet, so I didn’t know that for a fact. I also didn’t understand how that could be, because I thought it had all been settled years ago – that they had done it – and what was there to decide?” Thornton told Newsweek.

Julie Markes/AP Photo

She continued, “Nobody knew why they did it. Everybody knew they did it, though, and I wasn’t sure whether they were there to prove they didn’t do it, or whether they were just there to tell us why. I just knew the basics.”

Lyle and Erik Menendez gunned down their parents, José and Kitty Menendez with 14 shots as the couple sat watching TV in the den of their Beverly Hills home on August 20, 1989.

The duo shot José five times, including once at point-blank range with a shotgun aimed at the back of his head. As Kitty attempted to crawl away, Lyle shot her in the face with a shotgun. In total, she was shot nine times.

Lyle, who was then 21, and Erik, then 18, admitted they shot-gunned their entertainment executive father and their mother, but said they feared their parents were about to kill them to prevent the disclosure of the father’s long-term sexual molestation of Erik.

Menendez Brothers’ First Trial

Two separate juries, each consisting of 12 individuals, were formed – one for Lyle and one for Erik. Thornton served on Erik’s jury. The court established separate juries to account for the potential differences in guilt between the two brothers.

It didn’t fully hit Thornton she was a juror in the Menendez case until she saw Erik sitting there in the courtroom, just a few feet away. He sat silently beside his attorneys, Leslie Abramson and Marcia Morrissey – a surreal moment she described as a “soap opera.”

Nick Ut/AP Photo

Unable to discuss the infamous case with anyone, Thornton turned to journaling almost daily, which eventually led to the publication of her book, Hung Jury.

Well-known defense attorney Abramson gained attention for her compelling defense strategy, which argued the brothers had killed their parents in self-defense after enduring years of abuse at the hands of José. The prosecutors argued she was using the “abuse excuse.”

The “abuse excuse” refers to a defense strategy in legal cases where a defendant claims past abuse – such as physical, emotional, or sexual abuse – justifies or explains their actions, particularly in cases involving violence or crime. Critics argue it is sometimes used as an excuse to avoid responsibility, while others believe it is a legitimate explanation for behavior driven by trauma.

AP Photo

Over the course of 85 days, from July 20 to December 3, 1993, the courtroom saw 101 witnesses take the stand and sifted through 405 exhibits, each piece adding another layer to the unfolding story.

Among the hundreds of witnesses – family members, friends, teachers, coaches, experts – Thornton said she will never forget Lyle and Erik’s testimonies.

“The ones that convinced me that they had a good defense case and that it should probably be manslaughter instead of murder, were the brothers themselves,” Thornton said. “I came down on the side of manslaughter, not murder, because I didn’t think the elements of murder, they could all be explained another way.”

Newseek/Courtney McGinley

‘The fact remains that I did believe them’

In an emotional testimony, the brothers recounted in vivid detail the horrific acts their father allegedly forced them to do – fondling each other, engaging in oral sex, showering together, “object sessions” with a toothbrush and later rape.

Lyle took the stand first, testifying he was scared, cried, and bled during the sexual encounters with his father, stating, “He raped me. I told him I didn’t want to do this and that it hurt me.”

Steve Grayson/AP Photo

“All I can say is either that boy [Lyle] is the best actor I’ve ever seen in my life or he’s telling the utter truth, because he’s sticking to his story like glue,” Thornton said in her book.

Several days later, Erik took the stand, and Thornton said he was far less articulate than Lyle, with Abramson struggling to get him to express his point.

Nick Ut/AP Photo

However, he finally broke down when Abramsom asked, “What do you believe was the originating cause of you and your brother ultimately shooting your parents.”

Erik responded, “Me telling Lyle…” He paused, crying, as his attorney asked another question: “You telling Lyle what?” Tears continued to roll down his face. “…that my dad molested me. I just wanted it to stop.”

“I had to be thinking, are they lying? Are they fabricating a defense because the defense asked them to? I had to be thinking that every second of every minute of every hour of every day, but the fact remains that I did believe them,” Thornton said.

‘The juries were devastated’

After all the witnesses testified and closing arguments were made on December 15, Thornton said the jury was ready to begin deliberations.

Abramson outlined the potential verdicts: first-degree murder, second-degree murder, voluntary manslaughter, and involuntary manslaughter.

Nick Ut/AP Photo

“I thought, well, I don’t want to have somebody’s life in my hands, it felt like a big responsibility,” Thornton said.

On January 13, After deliberating for 106 hours, Thornton said Erik’s jury announced a deadlock, and Judge Stanley Weisberg declared a mistrial.

The jury was evenly split – six men and six women – a dynamic quickly turned into a tense “battle of the sexes.”

“People afterwards claimed that the women were voting emotionally and that they were in love with the brothers and that they were too stupid to understand the jury instructions, when in fact, it was the men who were voting emotionally and pounding on the table and calling us names and trying to get us to vote their way, Thornton said.

Thornton continued, “I thought that the women were far more logical than the men were. They just weren’t buying it that a man could be sexually abusing his teenage sons.”

Thirty years ago, the juror said topics like child abuse were rarely discussed. Society’s understanding of these issues – and advancements in science and law – have grown significantly since then.

However, Thornton said, “There were so many other kinds of abuse and neglect that if you took sexual abuse off the table, it would still have seemed to us [manslaughter voters] there was fear in that household, and that they could have been killing out of fear at that very moment.”

Twelve days later, after 139 hours of deliberation, Lyle’s jury also deadlocked, leading to another mistrial.

Gus Ruelas/AP Photo

“The juries were devastated. We wanted to reach a verdict. We did not. It took us a month to admit we were not reaching a verdict,” Thornton said. “We deliberated every day, every work day, for a month, and could not agree. Some people say we didn’t decide. We each decided, but we couldn’t agree with each other.”

Trial one ended with two deadlocked juries, unable to agree on whether the brothers were guilty of murder or acted out of fear. This led to a mistrial on January 28, 1994, and set the stage for a second trial in 1995.

Menendez Brothers Second Trial

Prosecutors argued there was no evidence of the alleged molestation and the judge excluded most abuse evidence and witnesses, including Lyle, from the second trial. There was only one jury, unlike the two juries in the first trial.

“Lyle Menendez did not testify because he would have been impeached,” reporter Alan Abrahamson told Newsweek. “During the first trial, he talked to the woman named Norma Novelli and he was caught in some considerable lies. If he had testified, those lies would have come out in court, and that’s why he did not testify in the second trial.”

Novelli and Lyle spoke frequently on the phone, with Lyle believing she was writing a book about his life. However, Novelli sold the recordings of their conversations without his written or verbal consent. The recordings were later published as The Private Diary of Lyle Menendez: In His Own Words.

Additionally, during the second trial, the prosecution played tapes recorded by the brothers’ therapist, Dr. Jerome Oziel, in which the brothers confessed to the murders of their parents. However, unlike in the first trial, when the defense called him to the stand to address concerns about his ethical conduct – Oziel did not testify.

Nick Ut/AP Photo

Erik confessed to Oziel, revealing the dark truth behind the murders of Kitty and José, and Lyle was called to the therapist’s office to corroborate on October 31, 1989.

Oziel confided in his mistress, Judalon Smyth, about the confession. Several months later, Smyth went to the police with the chilling details of the murders.

“I don’t even blame the second trial jury for having reached the conclusion of murder, because they were not allowed to consider manslaughter,” Thornton said. “They were not allowed to hear the same defense that we did.”

In July 1996, both brothers were sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole. The verdict highlighted the complexity of the case and the differing views on justice and mental health issues in the context of violent crime.

New Evidence Emerges After Three Decades

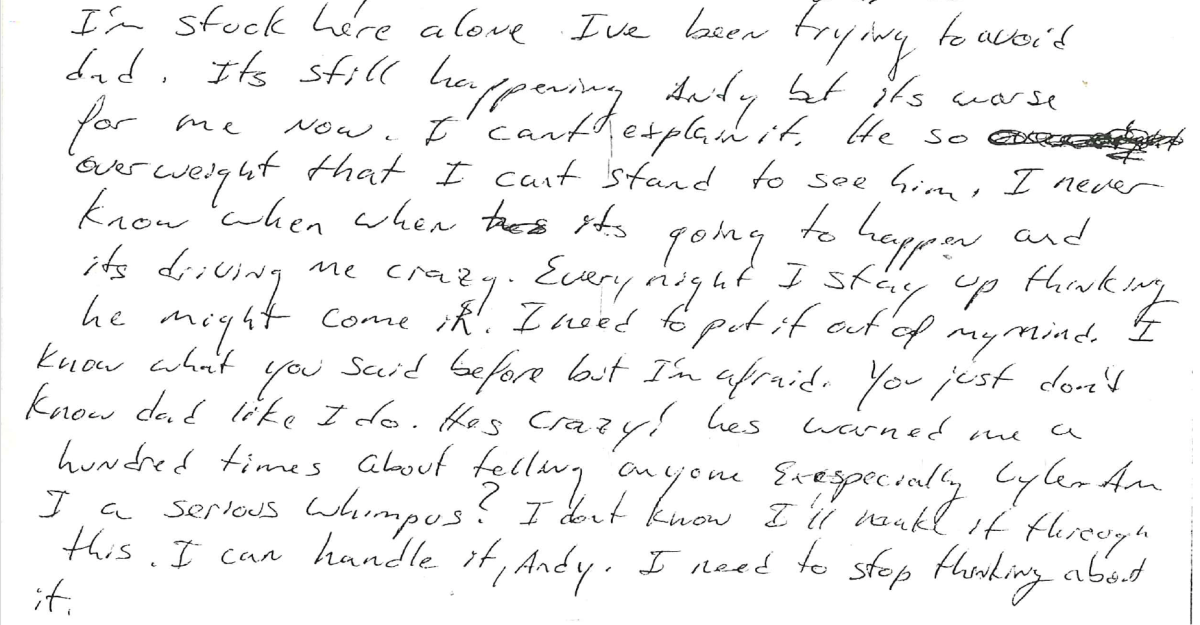

In May 2023, the Los Angeles District Attorney received new evidence, including a 1988 letter Erik wrote to his cousin detailing the alleged sexual abuse by his father. The evidence also includes a statement from a former Menudo member who claims he, too, was abused by José.

“It might have made a difference,” Thornton said.

Robert Rand

Thornton said testimony from former Menudo star Roy Rossello could have helped, as he was the only other person who could speak firsthand to the sexual abuse, aside from the two brothers.

“If we’d had those two pieces of evidence – that would have been an additional person to vouch for the sexual abuse,” Thornton said. “And the letter would have shown they didn’t just make it up after the killings. Andy Cano could have been there to say, ‘Oh yeah, I remember this letter, or I presented this letter myself.'”

What’s Next?

Lyle, 56, and Erik, 53, have spent three decades behind bars. Now, it’s the Menendez brothers’ turn for a potential chance at freedom.

California Dept. of Corrections via AP

On October 24, Gascón announced plans to recommend the Menendez brothers’ life sentences without the possibility of parole be replaced with a 50-years-to-life sentence for murder. He said, due to their ages at the time of the crimes, they would be eligible for parole immediately.

“I would like for him to have started right out with: ‘We’re asking for manslaughter.’ He didn’t do that, but he did point out that the laws have changed. I’m rooting for their path to freedom,” Thornton said. “I do think they should be released.”

The court has set a date for Erik and Lyle Menendez on December 11 at the Van Nuys Courthouse, where the brothers previously faced trial in 1993 and 1995.

Do you have a story Newsweek should be covering? Do you have any questions about this story or the Menendez Brothers? Contact LiveNews@newsweek.com