Divinity: Original Sin II nearly killed Baldur’s Gate 3 in its infancy. Yes, Larian’s breakthrough 2017 RPG proved the developer had the chops to take on a legendary series, and provided the foundations for an astonishingly open-ended Dungeons & Dragons adventure. Yet it almost robbed the studio of its opportunity to ascend to the mainstream.

By August of that year, company founder Swen Vincke had already landed a deal with Wizards Of The Coast to make Baldur’s Gate 3, but when the time came to provide the publisher with a design document, his team had nothing left in the tank. Deep into the final phase of Divinity: Original Sin 2’s development, all of their creative energies had been spent. Nonetheless, they knew they had to pull something out of the Bag Of Holding. “We need to write something, guys,” Vincke said at the time. “Or we’re going to lose this deal.”

Vincke and a small party of colleagues locked themselves in a hotel meeting room over a weekend and hammered out a design doc. “It was really bad,” he says. “But we didn’t have the brainpower to deal with it, because we were trying to do D:OS2. Wizards then sent it back with the corporate equivalent of, ‘This is really shit’. And we said, ‘We know, but we’re releasing a game – don’t ask us to make this now. Give us an extension’. Luckily they understood, and so we got another chance.”

Why was Larian pushing so hard to secure a venerable, ancient videogame licence for itself? “It’s one of those IPs that you know a lot of people will want to work on,” Vincke says. “So it would be great for attracting other people to the studio.” The CEO had watched his company grow internationally during the making of Divinity: Original Sin 2, and decided he would need an outside property in order to maintain that momentum.

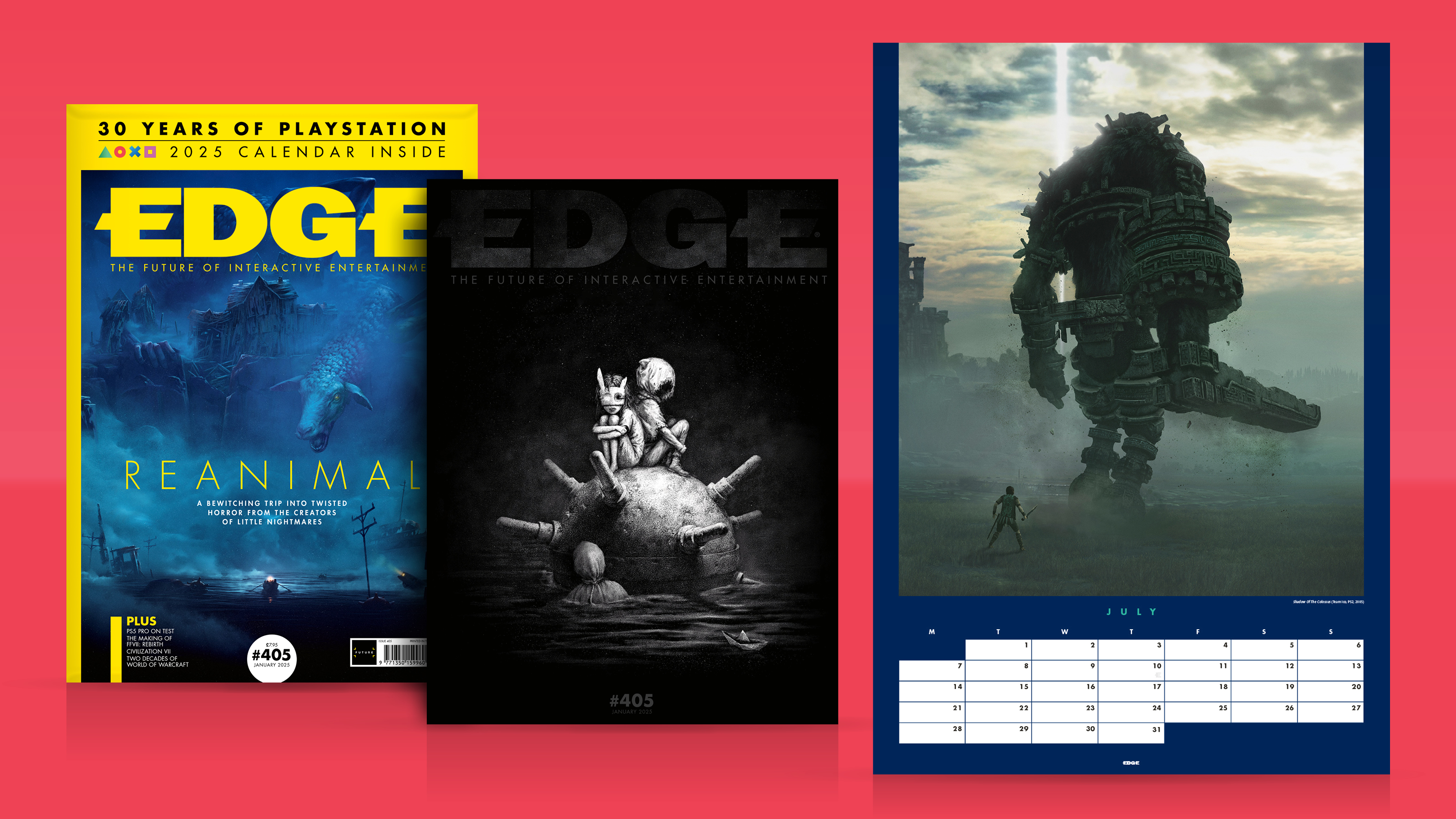

Subscribe to Edge Magazine

This feature originally appeared in Edge magazine. For more in-depth features and interviews diving deep into the industry delivered to your door or digital device, subscribe to Edge or buy an issue!

“I felt like there was a glass ceiling that we wouldn’t be able to break through unless we had triple-A production values, budget, marketing, all the triple-A things,” he says. In his mind, there were only three big RPG properties that could help Larian go forward as it needed to. “It would have been Ultima, it would have been Fallout, it would have been Baldur’s Gate,” he says. “There was not a lot to choose from.”

Beneath all this strategy, however, was a personal connection. Larian’s first project, a cancelled RPG named The Lady, The Mage And The Knight, was developed during the same period that BioWare worked on Baldur’s Gate in the late ’90s. “We knew about them,” Vincke says, “and were watching what they were doing.” A fan had even attempted to put the two studios in touch – before Larian’s then-publisher halted it, frightened about losing important trade secrets to a competitor.

“I should have been talking to these guys, but then the relationship had soured because of this intervention,” Vincke remembers. “That was a real pity.” He subsequently played and adored both of BioWare’s Baldur’s Gate games: “The one thing they didn’t have, that was very important for me, was the dynamic environment where you could interact with the world.”

It’s that marriage of RPG storytelling and deep simulation that Larian ultimately defined as its own voice, and which won over writing director Adam Smith – who was working as a journalist at the time of Divinity: Original Sin 2’s release. “From its origin stories to its brief emergent narratives,” he wrote in a glowing Rock Paper Shotgun review, “few games let you take part in better tales than this one.” Taking on the lead writing gig for its followup was, as you might imagine, daunting.

“It was the dream job,” Smith says. “But with the huge dose of reality that it would really suck if it sucked.” He joined as employee number 12 of Larian’s Dublin studio, and watched as the company expanded around him, setting up a cinematics department from scratch. “You realised very quickly, ‘Oh, this studio is going to be unrecognisable in a few years in terms of the faces you see, because it’s going to grow so much’,” Smith says. “And then there’s the anxiety about that. How will it change?

Will it lose its identity? Will it transform into something different? All of that runs through your head. You think, ‘Did I arrive at the right time or the wrong time? There’s a good chance that all of the new people coming in now become the people who fucked up the next game from the people who made Divinity: Original Sin 2’.”

“I realised it didn’t have to be that much of a change, because we had a lot of freedom.”

That first couple of years was “really weird” – the initial fear compounded by respect for the original Baldur’s Gate games. “Reaching back that far and saying, ‘We think we can take this on’, it was a statement,” Smith says. “And it’s because we had a story that we felt was good and fit that world.”

The Divinity universe was Vincke’s own creation, a bloody yet playful high-fantasy setting that Larian had worked in consistently since the millennium. At first, it was difficult for him to step away and embrace the communally created D&D world of the Forgotten Realms. “But then I realised it didn’t have to be that much of a change, because we had a lot of freedom,” Vincke says. “So we could turn things when we needed them to turn.” That realisation came with the help of Wizards Of The Coast, which told Larian: “You are the dungeon masters here – it’s your story.”

Larian became comfortable with pulling on tiny existing threads of lore and spinning them out into grand new tapestries. For example, Moonrise Towers, the gloomy fortress that forms the centrepiece of Baldur’s Gate 3’s second act, was based on a “singular entry of two phrases” in existing D&D literature. Even those scant details proved malleable. “We could do whatever we wanted with it,” Vincke says. “It did say in those two phrases that it was two towers. For a long time, the second tower was actually there in the level. But at some point we said, ‘We just need one tower’.”

A changed setting wasn’t Larian’s biggest new obstacle, however. The Baldur’s Gate 3 team was conscious that, for many developers in the past, the adoption of cinematics had meant cutting back on player choice, character variety and multiplayer – some of Larian’s calling cards. “Swen said, ‘We only do this if we don’t compromise for it’,” Smith recalls. “‘If any of that is necessary, then we don’t do it.'”

In the subsequent years, the studio figured out a compromise-free route to a deeply cinematic RPG, tackling the many problems as they emerged. “From my point of view, writing a narrative, the scariest moments were always with cinematics,” Smith says. “How do we make sure this works if a character’s already dead – a character we just did a whole mo-cap session for, with a very famous actor? It was intimidating.” At times, Smith became aware of just how fragile an experience they were assembling.

“Because we’re putting all these systems in play,” he says. “We have a very complex narrative in terms of its structure: we’ve got four people running around at the same time, and they’re chaotic RPG players. They don’t give a shit what you want them to do – they give a shit what they want to do.” With the addition of cinematics, the expense of catering to that player whim became much higher. “It’s not just editing a line,” Smith says. “The time cost of everything is more. But we pretty quickly got into a groove with it. The ethos of Larian is very much ‘keep doing it until it’s good’, and that didn’t change. That was great, because that’s one of the things you could compromise on. You could say, ‘OK, it’s good enough’.” Larian’s art team grappled with the impact of close-up cinematics, after years of working exclusively with a zoomed-out tactical camera in the Divinity: Original Sin games.

“The biggest problem is that things that look good from far don’t necessarily look good up close,” explains art director Joachim Vleminckx, a Larian veteran of almost two decades. “We always had this struggle of, ‘Oh it’s so noisy’, but when you zoom in it looks perfect. With cinematics, you can zoom in on an eyeball and see all the details.” Vleminckx often wondered: was Larian making a top-down game with cinematics, or a cinematic game in which you happened to be able to zoom out? “It’s been a very hard struggle to get it balanced.”

Another question Larian’s devs regularly asked themselves was whether or not they were making Baldur’s Gate 3 for fans of the original BioWare games. “In reality, not really,” fellow art director Alena Dubrovina says. “Because we’re making it for a modern audience that are young people like me, so they probably haven’t really played the first or second game. We really wanted to make it so that even if you don’t know D&D or Baldur’s Gate, you would still have exciting choices as a player, visually and narratively, and be able to enjoy the experience.”

That’s not to say there wasn’t baked-in enthusiasm for Baldur’s Gate at Larian. When Vincke announced the deal with Wizards Of The Coast internally – visiting his studios one by one – there were “three reactions in the room”. Some staff had never heard of Baldur’s Gate before, others were ambivalent, but the majority of employees were “super-elated”. Smith was one of those with a deep connection to the original stories. He and the narrative team made great efforts to carry forward the characteristics that made Baldur’s Gate distinct. “During the whole of early access, I remember reading a lot of comments from people like, ‘It’s good, but it’s not Baldur’s Gate’,” Smith says. “And we were like, ‘Just have a bit of faith – we know what we’re doing on that front’.”

The GR review

In our Baldur’s Gate 3 review on GamesRadar+ we called it “a new gold standard for RPGs”

While Larian’s sequel is set a century after the events of BioWare’s games, it dives with glee into the familiar theme of dark inheritance. Where BioWare’s protagonist was in line for the throne of the god of Murder, Larian’s shares their brain with a mind flayer tadpole. Both had the option to embrace the powers that came with their gift, or to reject them as a curse. The dynamic was reflected elsewhere, too – in companions who wrestled with their own dualities, and in the Dark Urge origin story, which optionally cast the player as a secret serial killer.

“The Dark Urge was the bit I wish we could have screamed about from the rooftops for the longest time, but it was also the rest of them,” Smith says. “You’re all people who have the darkness inside and say, ‘Can I use it for good?'” What the player goes through with their illithid tadpole, the parasite in their head, is reflected in the emotional traumas of the members of their party. “It’s the baggage that you carry with you and the damage that’s been done to you,” Smith says. “Whether it’s Astarion’s vampirism or Karlach’s heart, they’re all people who’ve had something taken from them, and that can bring out the worst or the best in you. That to me always felt very Baldur’s Gate.”

You can see that pain in the companions Larian chose to bring forward from BioWare’s games, too – 124 passing years being no obstacle to long-lived elves or barbarians magically frozen as statues. Even before the original Baldur’s Gate games concluded, Jaheira and Minsc were both grieving for romantic partners as they swung away at gnolls and drow.

“We didn’t have access to all the legacy characters, purely because we wanted to be honourable to the canon of it,” Smith says. “But Jaheira was the one who really tied it together and always gives me that warm, tingly Baldur’s Gate feeling. To me, there’s something very heroic but tragic for Jaheira to be reminded of the worst times in her life. She’s back travelling with a Bhaalspawn again, and the last time this happened her husband died.”

In one key respect, Baldur’s Gate 3’s storytelling is fundamentally different to that of its predecessors – no matter how much thought was given to canon and consistency. While BioWare’s games were literary propositions that dealt primarily in boxes of text, Larian was now writing cinematic dialogue.

“If you take the dialogue directly from a game that wasn’t meant for cinematics and put it onto a cinematic character, it will often feel very different – dry, like a book on tape,” Smith says. “And the more cinematic tools you have, the more you need to actually know how to use them. It becomes easy once you do. Cinematic dialogue is incredibly liberating, because you don’t need people to say out loud what they’re thinking – they can do it with a facial expression or a gesture.”

Once Lae’zel was responding to the player with a wordless eyeroll, it was clear Larian was in new territory. If a Baldur’s Gate 3 character does speak in a flowery, literary manner (as the devil Raphael does, for example), it’s only because they’re a pretentious showoff. “Raphael is a theatre kid with too much power,” Smith says. “The worst thing in the world.”

It’s evident that cinematics were a project-spanning headache for Larian, spiralling out into multiple departments and pushing developers to tackle their disciplines in new ways. But for Vincke, their inclusion was worth every difficulty. “From where I was sitting, coming back to my strategic ambition for Larian, this made perfect sense,” he says. “If we were going to bring a game like Original Sin 2 to larger crowds, we would need to have triple-A production values, whatever that takes. Because it’s only then that we’re going to discover if there’s a market for this type of game.” That is, a cinematic RPG that doesn’t use production values to “cover up the fact there is no choice”.

Larian scaled up to make its cinematic dream happen – but Vincke doesn’t believe the decision accounted for an elongated development time: “I think that COVID and the war added much more.” While the company set up new offices during the development of Baldur’s Gate 3, it also closed one, in Russia, after Putin invaded Ukraine.

“I had already thought about what we were going to do if it actually happened,” Vincke says. “So the decision was instant: we can’t stay there. We needed to move people away because, as these things go, you can almost predict that eventually there’s going to be a mobilisation, and that meant that all my team was going to go to war.” Rather than wait for colleagues to be drafted into the military, Larian set about facilitating their exit. It took the efforts of a joint task force, made up of the developer’s studio operations, finance and legal teams. “They did an incredible job, worked day and night to be able to get every single person a tailored solution to get them out of there,” Vincke says. “I’m super-proud of them for doing that.”

Over 90 per cent of the St Petersburg team was relocated to other Larian studios. “That meant that we started fighting with embassies and consulates,” Vincke says. “It was really complicated.” Colleagues set about welcoming the refugees to new countries, helping them to adapt to their suddenly changed circumstances. And, understandably, work fell by the wayside.

“In a machine as complicated as an RPG, where everything’s connected to everything, if you suddenly start ripping stuff out, the entire thing collapses,” Vincke says. “Because things that were supposed to be done are not being done. It’s not that they didn’t try, but it was really, really hard. You could see the ripple effect of that lasting all through the end of development.” The delays meant compromises and cuts to Baldur’s Gate 3. “It always happens,” Vincke says, “but it’s rare that you lose a studio in the middle of development.”

We all know, of course, that despite the growth and contractions, the design doc deadlines and the hard lessons, the story ends well for Baldur’s Gate 3. Larian’s runaway success story – critically, commercially and with a fervent D&D community – has been impossible to miss. In fact, almost a year after the game’s launch, the round of applause has yet to subside.

“The award season is still going on, which is really weird,” Smith says. “It’s incredible. The only time I’ve got super-emotionally overwhelmed by it was when we got Game Of The Year at The Game Awards. In that room with us were Swen and a few other Larian people who’ve been around a lot longer than I have. Seeing them go up, after decades, was a lot. I was dressed in my little bear onesie, crying. That was really moving, because it did mean a hell of a lot to them.”

Vincke now understands why rock stars get so tired. “Because it’s too much,” he says. “I think it’s great that you have a moment of celebration, but we still have award shows that we’re going to. Because they’re important, and we really appreciate it, but it would be cool if everybody could agree to do it all at the same time.” He emphasises again that Larian is incredibly grateful. “But it is surprisingly draining on the soul. I certainly didn’t expect that. I think we’ve all been more emotional because we can’t get closure. And you want to have closure at the end of a project.”

Characteristically, Vincke has started to formulate a strategic approach. “We sent rotating teams,” he says. “So different people went to different award shows. It affects development – there’s a lot of them.” He laughs, but he’s serious. “This has been a real problem.” As our conversation with Vincke comes to an end, we resolve to leave Larian alone for a little while – both to plot its next projects, and to close the door on Baldur’s Gate 3. Like the companions at camp, the studio has plenty to process.

Looking for what to play next? Take a look at our list of the best RPG games!