It’s hard to think of any term that has had such an impact on the videogame industry as ‘triple-A game’. Yet for all its power, it’s one we take for granted. Today, ‘triple-A’ is simply part of the furniture, remaining an everyday term despite the massive shifts in how videogames are made, distributed, played and understood over the decades since this buzzword first emerged.

But when was that, exactly, and where did it come from? Our investigation into the label’s origin, in search of a patient zero, swiftly becomes an investigation of its origins, plural. This term has been adopted by multiple generations of developers, working in different regions and disciplines, its exact meaning dependent on that context. So, is there a solid definition of ‘triple-A’ to be found today? And, after a long time at the top, might it finally be time to retire the term for good?

Revolution Studios co-founder Charles Cecil remembers first hearing the term during a visit to Virgin Interactive’s offices in Orange County, California, in the late 1990s, following the release of the original Broken Sword. “The game had done phenomenally well, particularly on PlayStation,” Cecil recalls. “And Martin Alper was their CEO, and he very kindly took me out for lunch. And he talked about ‘triple-A games’. And then he said to me, ‘The reason I make such great purchasing decisions is that I’ve never played a videogame’.” Cecil says this dismissiveness was typical of publisher executives at the time. “They had a contempt for the medium. And they thought that actually what people really wanted to do was watch movies interactively.”

‘Triple-A’ meant little to Cecil, but he looked it up after the lunch and identified it as a borrowing from US credit rating systems, where the term is used to indicate a bond with the very lowest risk of defaulting. Here, it was being used as shorthand for “we’re going to put so much money into this game that it can’t fail,” Cecil says.

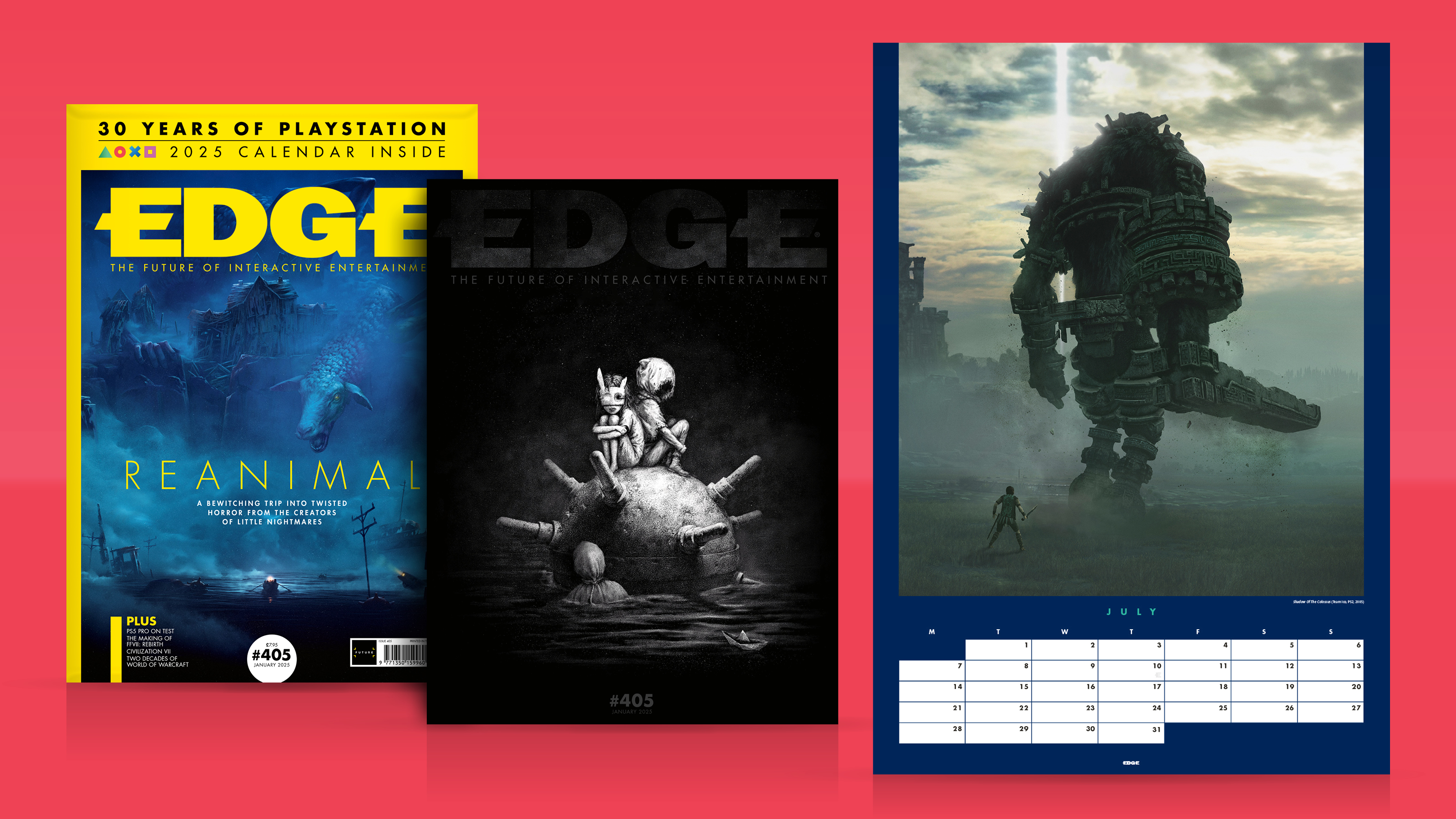

Subscribe to Edge Magazine

This feature originally appeared in Edge magazine #396. For more in-depth features and interviews diving deep into the gaming industry delivered to your door or digital device, subscribe to Edge or buy an issue!

He quickly came to associate the concept with arrogance and corruption. “In the late ’90s, there were some terrible things going on,” he says. “A number of publishers basically said, ‘For every dollar we spend on internal development, we’re going to account for a profit of three or four or five dollars,’ or whatever. Virgin in particular had a lot of internal development, and they were posting huge profits, and that was fine, as long as you never ship the product – and by god, you never can it, because then you take an almighty write-off.”

While Broken Sword was a success, Cecil remembers this as a “very bleak” period for studios in Revolution’s position: “There was no sense of creativity, and British developers were very much marginalised because our big publishers, they basically sold out to the French or Japanese or the Americans.” Cecil admires many latter-day ‘triple-A’ games, particularly the Grand Theft Auto series, but he continues to regard the concept itself with derision. “It’s a stupid term. It’s meaningless. And I think it came from that era, which I don’t have very fond memories of, when everything changed, but not for the better.”

When ID@Xbox director Chris Charla first heard the term, as a journalist in the ’90s, it was in the form of a putdown. “I was working at Next Generation, the US version of Edge, at the time,” he recalls. “And the way it was said to me was in the negative. Somebody was talking about a game they were bringing, a PR person: ‘I mean, it’s not a triple-A game, it’s just a platformer’. Dot dot dot. And I remember it distinctly because I was like, ‘What’s a triple-A game?'”

During his time as a journalist, Charla seldom used the term, and still regards it as a bit of a black hole. “It’s a squishy term to nail down and define,” he says. “It ends up being much more impactful when it’s used in comparison, like the first time I heard it.” As for its origins, Charla agrees with Cecil’s assessment, that ‘triple-A’ was primarily derived from credit ratings. There’s also an association, perhaps, with the Golden Age Of Hollywood ideas of ‘A films’ and ‘B films’, though Charla suggests any connection there is “retconned”.

Indeed, Terra Virtua CTO Kish Hirani – a 20-year veteran whose credits include a stint as PlayStation’s head of developer services – suggests that ‘triple-A’ was actually an effort to distinguish games from movies. He once again points to the term’s origins in the credit industry. “And somehow, that became our word. You would have thought we would have ended up using the movie industry term ‘blockbuster’, which is easier to say. But it was all about money.” Hirani argues that the preference for ‘triple-A’ over ‘blockbuster’ reflects a younger industry’s desire “to differentiate ourselves from this older medium”, while simultaneously aping its production values.

It’s a point echoed by Three Friends co-founder and former Mojang business developer Daniel Kaplan, who spent years haggling over potential publishing deals with ‘triple-A’ companies after joining the Minecraft studio in 2010. But in all his backroom dealings with giants such as EA and Ubisoft, he was never offered a definition more exact than “most expensive” – whatever that looked like at the time. Like Hirani, he thinks the term speaks to an underlying insecurity: “The gaming industry felt like it was the underdog during the late ’90s, and the beginning of the 2000s, trying to compete with the movie industry. And it felt like they put the triple-A label on themselves to reflect that they were big business.”

Regardless of its original derivation, the term ‘triple-A’ has accreted many other meanings since inception, much as ‘B-movie’ has evolved from accounting designation to a broad-yet-recognisable cinematic subgenre. In the hands of younger developers who entered the industry in the ’00s, it has become a complex cultural designation and status symbol with specific associations, from narrative and art direction through to hardware format and country of origin.

Among that later generation was Alex Hutchinson, co-founder of Typhoon Studios and creative director on Assassin’s Creed III and Far Cry 4. “I first heard it while I was still working in Australia, when I was just starting out, in the very early 2000s,” he says. For Hutchinson, as for many young devs at that time, ‘triple-A’ was a career ambition. “It was a marker of everything that we weren’t at the time. We were working on licensed Game Boy games for Activision, and that was the aspirational goal – to get into triple-A, and work on something with a big budget. And, you know, presumably high quality?”

“[Shenmue] was just monstrously large. And it seemed kind of inconceivable for us.”

For Hutchinson, one of the definitive triple-A games of the period was Sega’s Shenmue, with its unprecedented simulation of daily life. “It was just monstrously large. And it seemed kind of inconceivable for us. These are the days before thirdparty engines were very good, and so everything was bespoke. So if you’re working on a Game Boy game, and you see Shenmue on the Dreamcast, the delta between those two games is so immense that I think it was sort of inspiring.” This is indicative of the kinds of games and developers he associated with the term, having long shed any links to the US-based finance industry – and, for Hutchinson at least, becoming synonymous with another part of the world.

“For me, triple-A referred almost explicitly to Japanese games at the time,” he says. “Capcom, Nintendo, Sega.” This was in part, Hutchinson argues, because Japanese developers were the first to figure out how to do game development “at scale”. “If you think about the UK scene, or the Australian scene, they came out of bedroom coders, those sort of one-man shops,” he says. “The Japanese scaled up through Nintendo and Sega, all that sort of stuff, so they had blockbusters first.” It was only in the mid-2000s, by his reckoning, that the US and Europe caught up, something he puts down to Japan’s continued commitment to “working on bespoke technology”, which produced great results but could mean building from scratch with each generation.

With that in mind, it’s perhaps no surprise that many of our interviewees agree on the PS1 era as the period during which ‘triple-A’ first took hold in the industry. Its ascendancy goes hand in hand with the wave of console gaming that followed Sony’s entry to the market. “I don’t remember the term being used in a lot of my earlier gaming,” says Sharkmob associate art director Sam Hogg, who since joining the industry in 2008 has worked on Forza Horizon, Fable and Everwild. “The early consoles, like the Sega Mega Drive, that kind of era – the terminology didn’t exist back then.” Hogg jokes that Microsoft, Sony and Nintendo may have conspired to normalise the term, in order to big up their console exclusives.

When Hogg later questions whether the concept can be traced back to “a flagship title for a particular console”, there is one suggested by several of our interviewees (Final Fantasy 7) that seems to fit neatly into the timeline being pieced together here. But if there ever was a ‘first triple-A game’, the term has long since transcended any single template or genre over the subsequent decades – in the process creating endless debate in studios around the world.

“I think we as developers struggle to define what triple-A means,” admits James Dobrowski, founder and managing director of Sharkmob London. “I actually think that the terminology causes more confusion to developers than is healthy right now.” And yet, when Sharkmob set up its London studio in 2020, its stated target was to make ‘triple-A’ games. “We’ve had so many conversations around that term,” Dobrowski says. “To the point where we started putting games on the table, going, ‘Do you consider this triple-A?’ And you’d get entirely different answers across the team, including in our management groups.”

He picks one of many edge cases to illustrate his point: “Was World Of Warcraft triple-A when it first launched? And is it still triple-A? From a budget and a scale of team perspective, yes, 100 per cent. And the quality bar was at the top of what was being released within the MMO genre.” But, of course, it’s all a matter of perspective. “If you ask somebody who spent their career working on God Of War, the Uncharted series, those kinds of really high-end, high-fidelity narrative singleplayer experiences, they’d all say no.” There’s a divide, he reckons, between those who define the term by the size of its development budget and team and those who go by “production-value qualities”. While the latter of course tends to follow the former, Dobrowski notes that it introduces considerably more nuance into the assessment – not least because of the ways that technological advances have blurred those lines in recent years.

The former camp are closer to the ’90s-originated definition, of a project with a budget so high that it supposedly guarantees success. Still, what counts as a high budget can vary enormously according to region and format. “I remember distinctly when I was at Sony, it was very problematic to explain to developers that a triple-A game on PS Vita was not the production-value level of a console triple-A game,” Hirani says. “A triple-A game on Vita was a quarter of that budget, or whatever proportion, but you’re still calling it a triple-A mobile game.” The same thing happened, he says, with VR. “When we say it’s a triple-A budget on VR, they’re like, ‘Oh, we’re not quite sure where the platform is going – how can we put up that level of budget?’ Because that was associated with what a console triple-A budget would be.”

Attempting to identify triple-A games by any particular feature or mechanic, meanwhile, reveals how different everyone’s personal definition of the term is. Dobrowski associates it with third- and firstperson camera perspectives, a definition that would exclude some huge, influential games of the period, particularly RPGs. Hirani, meanwhile, insists that fancy visuals are more important than expensive music, contending that Sony’s original Wipeout was never considered a triple-A title despite its brilliant licensed soundtrack. Hogg similarly puts graphical considerations at the forefront – unsurprising, perhaps, given her chosen discipline – but also suggests that it needs to be “slightly more high-octane, action-driven”, which she admits would rule out Kena: Bridge Of Spirits, a game Hogg nonetheless feels has “triple-A” visuals. And what about length – does it matter? Hutchinson reckons so. “Even if you do something that is incredibly high-quality, if it’s under ten hours, I don’t think anyone would ever call you triple-A,” he says. “Which is a bit strange.”

It’s perhaps inevitable that our most precise definition comes from QA, that thin red line between developer and audience. Victoria Emma Tyrer has worked in the space since 2017, at PlayStation, Firesprite and now Wushu Studios. From Ghost Of Tsushima and Horizon: Call Of The Mountain to Blood & Truth and State Of Decay 2, Tyrer has worked on games that most would consider firmly triple-A and others that arguably straddle the line. While there are many horror stories about the labour of QA and testers on big-budget projects, Tyrer has largely enjoyed the experience. “From a dev QA standpoint, triple-A games are by far the most demanding yet rewarding projects to work on in the game industry,” they say.

Tyrer offers a neatly compressed assessment of this oft-nebulous term: “Any game which exceeds 19 hours of gameplay to fully complete, has a lot of exploration for the user to engage with, allows the user to customise their gameplay experience through their character or skill set, and potentially has a large fanbase of players who would attend conventions dressed as their characters.” You’d be hard-pressed to find a more robust definition – and if it brings to mind a host of exceptions, past and present, then perhaps it’s worth considering what value this ’90s-originated term has here in 2024. Is it time we let go of ‘triple-A’ altogether?

“Those are the launches that end up on the evening news.”

After all, the idea of big-budget games as any kind of ‘dead cert’ has been tested in recent years. “Cyberpunk 2077, one of the most anticipated titles this decade, failed miserably at launch,” Kaplan says. “The latest Battlefield failed as well. You see it more and more often.” And if the term became a way at gesturing towards Hollywood ambitions, then that too risks becoming irrelevant, as relatively affordable middleware tools give smaller developers access to the kind of photorealistic graphics we might have once associated with ‘triple-A’. “It’s starting to fade out now, because the tools are out there for anyone to be able to create an incredibly realistic version of life or fantasy or whatever it happens to be,” Hogg says.

Charla, however, believes the term does have value for people with a close interest in games, “whether they’re community figures, fans, press or investors, to try and distinguish the biggest and the most important games”. In turn, these games can provide “huge cultural touchpoint moments”, he argues – concentrations of hype that get people talking. “The industry is so spread out now,” he says. “The game world is so spread out now. We all come together when there’s a triple-A launch, whether to enjoy it or to react to it.” That last bit might be slightly euphemistic – not every major release is warmly received, after all – but that doesn’t stop them from being focal points, for the industry and beyond. “Those are the games that poke up above the clouds, so that people who have never played a videogame in their entire life hear about it, whether it’s Call Of Duty or Spider-Man or Halo,” Charla says. “Those are the launches that end up on the evening news.”

But that sense of unity has a cost, and not just in how it makes cultural significance proportionate to budget. Hirani believes use of this ambiguous term in job ads – “‘Triple-A experience required’, when there’s no official list of triple-A studios or what triple-A games should be” – can deter would-be applicants. “Because it’s a made-up term, and especially if you’re a minority applicant, you just feel ‘I’m not good enough yet’, and you wouldn’t apply for that role. Which is a shame. Just because of that one word in a job description, we’ve missed out on that talent.”

Hutchinson points to how strange it is to talk to players in these financially derived “inside baseball” terms, contributing to a climate of false expertise. “We talk about the games to fans like they’re developers,” he says. “And so they respond almost like they’re developers, instead of talking about the finished product and the art form.” Nonetheless, many publisher executives continue to deal in ‘A’s.

As this article was being written, Ubisoft CEO Yves Guillemot, defending Skull And Bones’ $70 price tag to investors, described the notoriously troubled game as “quadruple-A”. There’s no financial precedent for this concept, which is obviously the result of a kind of linguistic arms race, but it’s not an entirely new term within the industry. Hutchinson first heard ‘quadruple-A’ shortly before he left Ubisoft in 2017: “It made me throw up in my mouth a little”.

Hutchinson, of course, no longer regards “triple-A” with the reverence he did as an up-and-coming developer. “When it first came in, it meant ‘quality’, and then it became ‘scale’. And now, I think, it almost means ‘bloat’,” he says. “When you started hearing ‘quadruple-A’, it didn’t make me think, ‘Oh, wow, it’s better’. It made me think, ‘Too much’.”

What’s next on the gaming calendar? Check out our upcoming games list for what to circle and, given the above, make sure you also take a look at the upcoming indie games list to highlight smaller projects too!